5.1. Theoretical background

| Site: | TOPPlant Portal |

| Course: | Training Manual for Plant Protection in Organic Farming |

| Book: | 5.1. Theoretical background |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Tuesday, 24 February 2026, 5:01 AM |

Theoretical background

Learning Outcomes:

- Explain the principle and main objectives of weed management in organic farming.

- Choose the appropriate combination of the preventive/cultural/curative practices for ensurement of effective weed management.

- Select and recommend a system-based, long term weed control strategy.

Principles of weed management in organic farming

One of the most important criteria for organic farming is to control weeds without the use of herbicides. To this end, all other elements of integrated weed control (agrotechnical, physical, mechanical, biological) and the elements of cultivation technology are protected against weeds by using as many elements as possible. The role of local climatic and soil conditions in the development of weeds is increasing compared to conventional farming. Thus, we have to consider with a unique weed flora in each organic farm. The most important principle of ecological weed control is not the destruction of weeds, but to promote the development and competitiveness of the crop with certain elements of cultivation technology at the expense of the weed by utilization of natural resources. The main goal of weed management strategies is to make the crop production system unfavorable to weeds, thus the harmful effect of weeds surviving can be minimized. For implementing effective results, a system-based, long-term weed control strategy is required to develop.

Weed control in organic farming cannot be performed successfully by a single method. Harmony of weed control and agricultural production must be found which does not constitute a step backwards, but represents a better, more advanced technology. Although maintaining weeds within an agricultural system is both harmful and beneficial, the aim of ecological farming is not to eradicate completely the weeds. As in all areas of plant protection, prevention is the most effective in weed control. This includes the use of weed-free, metal-sealed seed; well-treated, weed- and weed-free organic manure and compost; inhibiting the spread of weeds by keeping tillage, plant care and harvesting machines clean.

Knowledge on and importance of positive and negative interaction between crop and weed (background knowledge for further procedures)

The ecological role of weeds can be approached by a different point of view. The most commonly known harmful effects of weeds are to compete with crops for nutrients, water, light and space, to reduce the quality of crops, to increase production costs. However, weeds have some benefits as well. A balanced weed population can provide a favorable microclimate and the roots of the weeds can help to increase the microbiological activity and improve the structure of the soil. Weeds can promote biodiversity. Weeds are a source of nutrients for many insects. Although some of these insects are pests, others can be predators or parasitoids that can contribute to biological plant protection. Complete eradication of weeds can also mean that insects have no choice but to feed on the crop. Weeds can also be considered as indicator plants as they show the disadvantages and benefits of soil (applied nutrient replenishment and tillage).

The growth of the world's population requires higher food production, which can be achieved by increasing yields and applying a sustainable approach through responsible use of land and water and increasing food diversity. One of the objectives of integrated weed management is to maintain the weed population below the economic threshold by reducing the focus on eradication strategies and promoting a containment strategy for the potential increase in weed diversity. The ecological role of weeds can be approached by a different point of view. In conventional agricultural practices, weeds are declared as undesirable intruders that reduce crop yields and compete for limited sources. In this perspective, weeds force the usage of large amounts of human effort and technology to prevent even greater crop losses. On the other hand, weeds can be evaluated as beneficial component of agroecosystem that provide services complementing those obtained from crops in the following ways: (i) providing habitat for natural enemies of pests; (ii) reduction of soil erosion; (iii) provision of important sources of animal feed and human medicine; (iv) offering of habitat for game birds and other desirable wildlife species.

From the point of view of plant protection, integrated weed management has three main objectives:

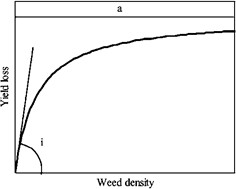

- a. Weed density shall be reduced to tolerable levels. Experimental studies describe a rectangular hyperbole for the relationship between crop yield loss and weed density (Figure 5.1). According to this mathematical curve, total elimination of weeds from crops is questionable. The same time, eradication efforts can be expensive and can result in harmful environmental damage and deprives living organisms including humans of ecological services. It is also indicated that this relationship is strongly influenced by various abiotical factors, such as weather and soil conditions. Thus, weed management is desirable rather than eradication.

Figure 5.1 Rectangular hyperbola (from Cousens, 1985a) that links the relative yield loss to the density of a weed species. Parameter “I” and “a” represents the initial slope of the curve and the maximum yield loss found with a very high weed density, respectively. -

- b. Reduction of the damage amount that a given density of weeds inflicts. Crop yield damage caused by weeds can be reduced not only by reducing weed density, but also by minimising the resource consumption, growth and competitiveness of individual surviving weeds. This can be approached by delaying or accelerating the appearance of weeds compared to the appearance of plants, by increasing the proportion of resources available by plants and damaging weeds with mechanical or biological agents. Accelerate the growth of the weed to mechanically or thermally control it in one step before the crop breaks through.

- c. Shift of weed community composition toward less aggressive, easier-to-manage species. Weed species act differently in their relationship with the crops. They differ in the degree of damage and of difficulty they impose on crop management and harvesting procedures. According to this fact, tipping of the weed community composition balance from dominance by noxious species within the agroecosystem toward a preponderance of species that crops can better tolerate is required. This can be performed by suppression (selective and direct) of undesirable species and then avoiding their re-establishment by manipulation of environmental conditions.

It is important to note that the most effective and economical weed control plan always requires several types of approach. In an ideal integrated weed management strategy in organic farming, it is essential to consider the cultural, mechanical and biological methods contained in the weed management toolbox and each component contributes to the overall level of weed control like several “little hammers”. Without this knowledge it is impossible to evaluate the impact of weed control tactics on a given weed population.

Weed control in ecological farming means a systematical approach for minimalization of the impact of weeds, optimalization of the cultivation and includes prevention and defense, as well. The ecological concept of “maximum diversification of disturbance” means to diversify crops and agricultural practices in the agro-ecosystem as much as possible in order to develop a long-term effective weed management strategy. This concept results in a constant disturbance of weed ecological niches and hence in a minimized risk of weed flora evolution towards the presence of highly competitive species. Moreover, a cropping system with high diversification reduces the possibility for development of herbicide-resistant weed populations.

Based on ecological concept, a weed management process should integrate preventive (indirect) methods and cultural/curative (direct) methods. Indirect category includes every method applied before a crop is sown (i.e. crop rotation, cover crops, tillage systems, seed bed preparation, soil solarization, management of drainage and irrigation systems and of crop residues), while the second includes any methods used during the crop vegetation cycle (i.e. crop sowing time and spatial arrangement, crop genotype choice, cover crops, intercropping, fertilization). Methods in both categories can influence either weed density (i.e. the number of individuals per unit area) and/or weed development (biomass production and soil cover). However, while indirect methods aim mainly to reduce the numbers of plants emerging in a crop, direct methods also aim to increase crop competitive ability against weeds.

Classification of cultural practices potentially applicable in an integrated weed management system, based on their prevailing effect are summarized in Table 5.1.

| Cultural practice | Category | Prevailing effect | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crop rotation | Preventive | Reduction of weed emergence | Alternation between winter and spring-summer crops, alteration between leaf and root vegetables and cereals |

| Cover crops (green manures, dead mulches) | Cover crop grown in-between two cash crops | ||

| Primary tillage | Deep ploughing, alternation between ploughing and reduced tillage | ||

| Seed bed preparation | False (stale)-seed bed technique | ||

| Soil solarization | Use of black or transparent films | ||

| Irrigation and drainage system | Irrigation placement (micro/trickle-irrigation), clearance of vegetation growing along ditches | ||

| Crop residue management | Stubble cultivation | ||

| Sowing/planting time, crop spatial arrangement | Cultural | Improvement of crop competitive ability | Use of transplants, anticipation or delay of sowing/transplant date |

| Crop genotype choice | Use of varieties characterised by quick emergence, high growth and soil cover rates in early stages | ||

| Cover crops (living mulches) | Improvement of crop (canopy) competitive ability | Legume cover crop sown in the inter-row of a row crop | |

| Intercropping | Reduction of weed emergence, improvement of crop competitive ability | Intercropped cash crops | |

| Fertilization | Use of slow nutrient-releasing organic fertilizers and amendments, fertilizer placement, anticipation or delay of pre-sowing or top-dressing N fertilization, nitrogen fixer plants as intercrop | ||

| Cultivation | Curative | Killing of existing vegetation, reduction of weed emergence | Post-emergence harrowing or hoeing, ridging |

| Thermal weed control | Pre-emergence or localized post-emergence flame-weeding | ||

| Biological weed control | Use of (weed) species-specific pathogens or pests |

A common problem concerning non-chemical methods is that effective control needs more frequently repeated treatments than chemical weed management in fact non-chemical tools mainly affect the aboveground part of the plants, whereas systemic herbicides kill the entire plant and therefore only require one or two applications per year. Different factors could affect the frequency of the treatments such as weed species composition, weed cover, weed acceptance level, weed control methods, climate and type of soil surface. For this reason, the integration of cropping and weed management strategies is vital for the future success of a farming system that relies on non-chemical methods of weed management.